Piecing together the past: the power that care records hold

As a new CELCIS briefing on developing practice on care records in Scotland is published, here we have curated where people with care experience have talked and written about their experiences of accessing and reading their records, what that has felt like, and what needs to be considered.

“Until I got my records I was emotionally disengaged from most things. I didn't have emotions to most things because I didn't know who I was. I never had that understanding, I never was taught who I was.”

Chris Marshall, a student, in this presentation, 'Write right about me', is talking about the records that are created, filed and archived, documenting details of the lives of every child and young person when a local authority has a responsibility for ensuring their care and protection.

Each record, box file, disc or Zip file, is unique and personal, and holds information, chapters of stories, and clues.

"Everybody wants to know who they are. Everybody wants to know who they’re connected to."

"Family is a set of disputed memories between one group of people over a lifetime. I sort of realised that at eighteen I had nobody to dispute the memory of me."

The power that care records hold

Who are you? What is your name? Where are you from? Familiar questions people ask, and also questions we often ask of ourselves when seeking to understand our identity and history. Sometimes the answers come easily, at other times the answers may not be as certain as expected.

Our earliest memories aren’t created in isolation. Those special moments – birthdays, outings, family times, are re-enforced through repetition and recollection from the people in our lives.

The poet and broadcaster Lemn Sissay has written extensively about this and his legal battle to access the information recording his childhood in care.

As he says in his TEDxHouses of Parliament talk, A Child of The State:

“I slowly became aware that I knew nobody that knew me for longer than a year. That is what family does. It gives you reference points. I am not defining a good family from a bad family. I am just saying that you know when your birthday is by virtue of the fact that somebody tells you when your birthday is, a mother, a father, a sister, a brother, an aunt, an uncle… it matters to someone and therefore it matters to you."

Lemn who came into care as a baby, had been told that his mother had abandoned him. When he left care and asked for his files he initially received only two pieces of information, information that would strike at the very heart of who Lemn is and his story. The first identified his real name – it was not Norman, the name he’d been known by all his life to then – and the second was a letter from his mother to social services pleading for his return. It took a further 30 years for him to receive all his records.

He’s not alone in his experiences. How this personal information is provided and what it says can have a devastating effect. What’s written and then read years later can be objective and distant but also critical and offensive. Award-winning playwright Louise Wallwein, recalls in a speech she gave to the Scottish Institute of Residential Child Care:

“I'll tell you a little bit about what's in my file it's entirely subjective and, quite frankly, says a lot of hurtful things such as 'Louise is an unattractive child who suffers greatly with her self-esteem because of her unattractive appearance. She has low self-image we are trying to help her believe she is not alone in her peculiarities.'

“A residential social worker who also happened to be a nun writes ‘Louise has ideas above her station. She fantasises about being an actor or a famous writer.'

“It's clear I was never meant to read this document.

“I'd forgotten just how desperate I was for love and connection.”

The information Louise Wallwein was given about her care came through a conversation with the nun who had first looked after her as a baby. She was able to give Louise information about her mother and her heritage. Louise says it was clear to her that Sister Philomena was counselling her, and this went beyond the years of her formal responsibilities, until Louise found her birth mother when she was 30.

The decision to access care records is not often an easy one. Revisiting or exploring the reasons for the state to take some responsibility for your care can be traumatic and unsettling. The potential to cast light on events that have eluded explanation, to find out more about yourself, and to help come to terms with the past, are compelling.

Charlotte Armitage, a student and campaigner, collaborated with the National Theatre of Scotland in a recording which explored creative writing and the impact that the arts can make within the context of care. When writing about the performance Holding / Holding On, she recalls:

“Aged 20, I embarked on a journey of post-traumatic growth, and that journey directed me back to the past; my past. I went through a process of learning every single detail about my life that I could so I could unpick it, analyse it, and then heal from it. This involved requesting and then obsessively reading every single record held about me and my life - social work files, court transcripts, and health records. After doing this I felt a weight shift, and my self-awareness and acceptance grew. I felt at peace with my past and what I had experienced in childhood.”

Older care experienced people may discover something they had forgotten or, just as likely, that they were never told. Records often written by professionals to share and document information, prioritised the purpose of suggesting or supporting a course of action in the knowledge that these decisions would be scrutinised and questioned. As a result, the voice of a child or young person, how they felt, and what they wanted at the time, is often missing, if it was asked. Read today, what is said in files can feel deeply wounding.

Is this me?

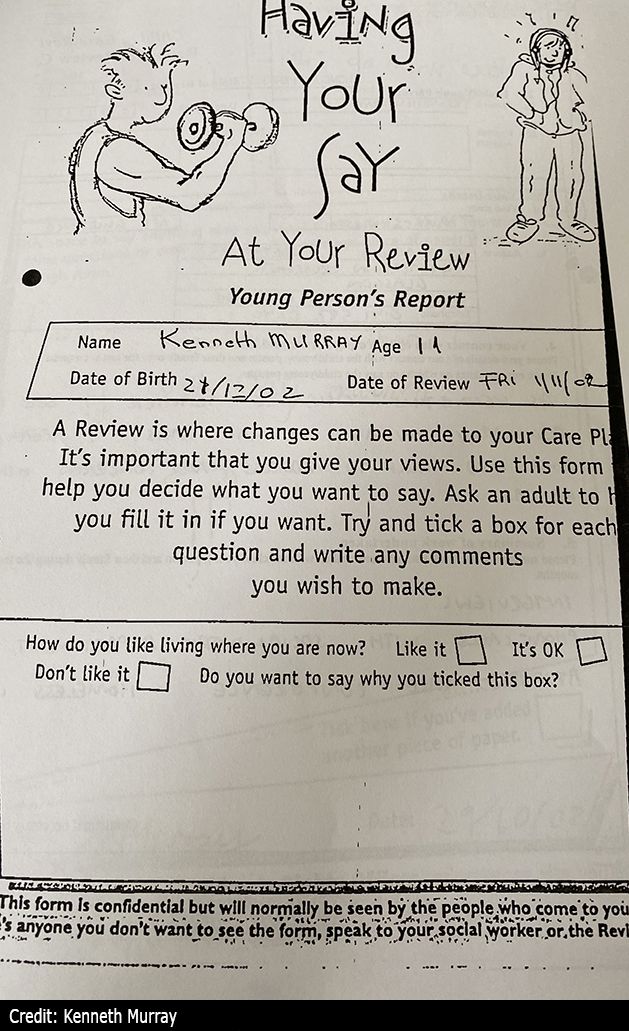

Kenneth Murray, who now works as a writer and campaigner for transforming the public understanding of care experienced people, also collaborated in Holding / Holding On, and recognises from his care records the description of the vocal child who knew exactly what he wanted and why. He regularly wrote stories then detailing how he felt about things, joined the school debating society, and made sure that everyone was aware of his views of the world.

Kenneth was 11 when he first went to live with foster carers. Separated from his family, his life began to be documented. Everything including his occasional visits with his brothers and sisters was noted down and filed away.

But when he saw these records years later, his view of his own history was also challenged by people he barely knew. Beyond the factual information about where he lived and went to school, the adults around him – the social workers, teachers and health staff - had also given their opinions of his attitude and character.

“According to one carer, I turned everything into an argument, which made them ‘glad to not be Kenneth’s social worker’. A teacher said I was exemplary in my understanding of language and this was demonstrated in my abilities in the school debating team.

“My records are full of conversations like this. Disputes about whether claims I was making were fact or questioning my motives in a way which seems odd when you remember I was eleven.”

This experience is familiar to that of author Kirsty Capes, whose records written about her when she was six years old, noted that her “aggressive behaviour has no apparent trigger”. As she further says in this article she wrote for The Guardian, the reports “pathologised” her childhood, making her seem very different from the version of herself that she remembered.

The place of care records

These official records are sometimes all a care experienced person has to make the fullest sense of their childhood, filling in the gaps that memory can’t. But records that provide opinion as well as dates, names and places, bring additional challenge.

While everyone has a right to see their records, doing so can take time, involve bureaucratic barriers, and once accessed, incomplete and new information can challenge a person’s memories, identity, sense of self and leave more questions than answers. As well as providing new information, judgemental comments in records can reframe the memories which had seemed secure and reliable.

When records are received, very often some information will have been blacked out, redacted. When you want and need as much information as there is, it’s challenging to understand why information has been withheld. Local authorities and other public bodies are bound by a duty of confidentiality to any third parties who may have been involved in a child’s life and could be identified in their records. These could be members of their family, social workers, teachers, foster carers or foster siblings – everyone important to in the life of the child and their care. Some information could be sensitive, for example, there could be medical information which the record holders may not have permission to release, or about someone who has not given their permission to be identified. The impact of this for the person looking to understand their story can be very shocking. Kirsty had to wait a year to see her records and recalls:

“Huge swathes of text had been redacted. Not just other people’s names and personal information, it seemed. As I scrolled, I saw that there were sections of 10, 20, 30 pages that were entirely blank, with a little note in red at the top of the page “third party”.”

But there are ways that the amount of redaction can be minimised, including how communication with the requestor could identify what is already known by them and lessen the need for redaction, or if those creating and archiving records can gain permissions early. The balance between prioritising a legal responsibility to prevent a data breach and providing information to the requestor needs active consideration. And care records are not alone in this. In the UK, legislation on Data Privacy, Freedom of Information and Subject Access Requests needs to consider the needs and rights of everyone concerned.

Who writes the story?

“Throughout my records it’s clear something is missing. My voice.

“Throughout the thousands of pages, there are only two pages which feature my voice and I only say one thing, ‘When will I see my Mum again?'

“At eleven years of age, I wrote that in every one of the measly boxes I was given to voice my opinion. Boxes which paled in comparison to the ones professionals were given to share their views. It was clear, my voice wasn’t important.”

Kenneth Murray's observation is not unusual. Now close attention is being paid to who is responsible for writing the records and how these are written.

Care records have long been kept as an administrative tool, a source and archive of information and point of reference for social workers and carers, used to record a child’s progress. These might contain, amongst other things, a child’s care plan outlining what is in place to support them, written welfare reports, reports for, and records of, reviews of the child’s plan, details of any arrangements made by the local authority, a chronology of significant life events, records of all contacts between the professionals involved and the children concerned and their family, decisions taken and reasons for these, social work assessments, outcomes of interventions and details of the child’s views.

That administrative focus has often resulted in written records littered with public service and social work jargon and acronyms, and language that can feel judgemental and institutional to a reader. Records might also be inaccurate, or describe the care leaver and their family in ways which are stigmatising and distressing to read.

Guidelines produced by Research in Practice for Adults for report writing advise that reports should be ethical, lawful, person-centred, proportionate, accountable and analytical. In this interview Gillian Lucas, an experienced social worker and Independent Reviewing Officer (IRO) explains how she thinks reports and case notes about children should be written.

What does it mean when official documents intended to be written and read by professionals to be factual and objective in documenting and explaining decisions taken about the care and protection of a child, are also the most personal, individual record of someone’s childhood? Though the facts are the same, there’s a world of difference between reading “James rarely goes to school and has no friends” and “This is James’ fifth school and he feels like he is always losing friends”.

Those responsible for creating the records need to keep in mind how the information they are noting now will affect the person or people who may read this in years to come. Beyond the scope of how they write about the kind of care young people have received in these records, how are they are capturing the young person’s perspective and the things that matter to them as they are growing up?

This poses a fundamental question: who owns these stories? Something that is now an active conversation in Scotland and something supported by The Promise of the Independent Care Review, published in 2020, which clearly sets out a number of expectations:

“Scotland must understand that ‘language creates realities’. Those with care experience must hold and own the narrative of their stories and lives; simple, caring language must be used in the writing of care files. The workforce must understand and be supported to consider the identities of the children they are working with, so children have a cohesive understanding of self and are able to hold their life experiences and understand them. These experiences should not define the course of their life journey. Life story work must always follow the lead of a child or young person and be therapeutic in its delivery and nature. It should feel normal and not create or compound stigma. The workforce must be considerate and write reports in a clear, relatable way, in plain English. Reports must be written in the assumption that the young person will read them at a later date.”

Over the last decade, practice has been changing. Reflecting on his own experiences, student Chris Marshall says:

“When I was being able to sit in the room to basically write my own records for an hour with member of staff it was enjoyable because I could put in what I wanted to put in there and I could see that throughout my records. The change from when I was in places where I couldn't sit with them and write my records, to when I was in places where I was more than welcome to sit and write my records, you can see the difference. It wasn't about all the bad things, they put more positives in it and that it was really useful for me as well; and even thinking back on it and there's a few members of staff who took the time to tell me what everything meant in it, so they would take the time to go over the records before they even sent them in.”

What matters in managing care records

Ensuring there can be an inclusive relationship in pulling together the story of childhood and experiences of care requires practices that can support the voice of the child or young person to be central.

Where records have not added insight into the early lives of the care leavers this causes great disappointment. Who Cares? Scotland and Aberdeen City Council have been speaking to care leavers about their experience accessing and reading their records. One person told them:

“I was looking for a missing piece of my jigsaw for something to tell me what was going on in my life in that time and I know what happened, I was there and I lived through it, so I think for me, it was trying to find that impartial piece of factual information so that I didn't need to take in my family's opinion and my family's lies.”

The experiences shared explain the hope that records might help to create a more positive narrative of time in care is undermined by gaps in the care timelines and negativity where records mostly focus on deficits or problems identified for children and families, and where things may have gone wrong in decisions taken or placement arrangements. Notable by their absence is what isn’t recorded: the good times, achievements and the moments a child or young person identifies themselves as important to them.

The records are a personal record. The sense that these should be understood as precious documents, written with love and knowledge about the young person, needs to be shared, as explained in this conversation 'Write right about me' for SIRCC 2020:

“I think when you start your healing journey and you're trying to recognize who you are as an individual there's so many questions and there's so many gaps in who you are and you're aware of the fact that the narrative and the rhetoric that you've been given by the people around you is that you have no value and you have no worth so care records are about filling in those gaps about what happened at the most traumatic and most impactful part of your life.”

All this insight has shaped how Aberdeen City Council, working with partners, continues to re-evaluated the way care records are produced there. Starting in early 2019 this work has looked at improving writing practice across all of the agencies in the area who contribute to the records for their children and young people.

In residential children’s homes in Aberdeen City, record writing has been made an integral part of the therapeutic and relational work that is done and is part of the council’s corporate parenting and children's rights agenda. It involves how carers write, including considering the use of language, empathy and love, children’s rights in records, co-production and collaboration in producing records, and maintaining high standards to ensure that young people will always have their voice heard and recorded in their care records.

One of the newer developments here has been the use and creation of ‘memory books’. Carers in Aberdeen are keen advocates of these and the process this provides for an opportunity for a young person and someone working to support their care, which whom they have a significant relationship, to make a memory book together. These contain shared happy experiences like going on trips and provide space for photos, drawings, cards and other mementos. This experience can help to talk through and, on occasion, provide some counter balance to events that might be causing distress or concern to a child or young person which will need to be mentioned in assessment records but in years to come could be detrimental to providing a more holistic understanding of someone’s childhood.

They also use an app which enables the children and young people to have a direct way of raising and inputting their own feelings about any given situation, concern or need they have, or suggest topics for discussion. For children and young people who might not be comfortable expressing their views in a meeting, for example a meeting to discuss the plan for their care, this means that their views can still be communicated, heard and recorded. All records are saved as uneditable PDF files, so what the young person feels and says remains on record without any interference.

Chapters in the story of life

Many artists and creators include and use their childhood experiences in their work, and it’s no different for writers with experience of care. What can shape these stories though is a desire to tell authentic stories of care and childhood, stories that can challenge the preconceived, fairy tale, superhero or ruined life narrative so often told on screen and in print.

Actor and producer, Sophie Willan, created the multi-platform literary project for care leavers, to share experiences in the form of short stories, novels and productions for TV, radio and theatre. Her most recent work is the BAFTA-award winning TV comedy series about a woman who is struggling to find her role in life. The story in Alma’s Not Normal draws on some of Sophie’s own experiences and shows the lifelong effect of care experience and family dynamics and the value of relationships. In an episode where Alma opens the box of her care records that have arrived on her doorstep, she too struggles to read what is said and match what her social workers wrote with how she remembers events from her childhood. Upset by the formal and objectifying language used, the judgemental words that casually find fault with the young Alma, she sees how she is written off as destined for failure. It’s a record of treating a child as a problem to be solved rather than a child in need of care and love. The experience is disorientating, really hard to process and leaves her questioning her own self-worth: “You read these and you just feel completely hopeless.”

Later as Alma attends an audition to join a theatre company in her pursuit of becoming an actress, noting that she is a care leaver, the director Jerry asks her about this and she tells him about just having read her records and how she is processing this. The director, it turns out, is also care experiences and says:

“I have always felt that us care experienced folk have got something special. We have navigated extreme circumstances, with complex traumas and gained skills and wisdom beyond our years. We have a huge capacity to love and heal and empathise, and I see that in you, Alma.”

Care records hold a power that is entirely unique in the lives of people with experience of care. The impact these have in helping to understand, validate and confront experiences, history, relationships and identity can never be underestimated or under-valued.

The understanding of the power of care records in supporting identity and the potential to address past traumas has led to a realisation that records must be created with honesty, transparency and love. Records are a living, human, story explaining a childhood and how a child or young person experienced their time in care. For every child, growing up will involve times joy as well as times of worry. It's clear that in making records, too often the people who care for children did not consider how important these will become to a person understanding who they are, their resilience and self-esteem. Now positive action is being taken to involve young people, and draw on their experiences, to create records collaboratively, with the wellbeing of the young person, both now and in their future, at their heart. Learning about what needs to happen to ensure that when people access their records they are getting what is right for them, is crucial in ensuring this experience can be more nurturing and less challenging.

The work in Aberdeen is just one example of how carers can work to produce inclusive and collaborative records with children and young people. The Developing Practice for Care Records in Scotland briefing produced by CELCIS, shares information about the research underway in Scotland to better understand the experiences of young people and adults accessing their records, and reflects the drive to develop good practice into the use, purpose and impact of records for them.

* Readers may find the content of this piece challenging and support for people with care experience affected by the issues raised is available from both Who Cares? Scotland, who may be able to link you into local support when accessing your records, and Future Pathways, who support any care experienced person who feels that they experienced abuse or neglect when they were in care.

"If I could tell that that little girl in my records anything, I would tell her, you’re going to be fine. You’re going to be more than fine, you are going to be fabulous."